If you’re a multinational you can easily bribe the people within Australia’s TGA to approve your product WITHOUT it even being tested.

With that in mind how can ANYONE trust the TGA?

Would you trust an airbag that hasn’t been tested or more importantly given ‘approval’ according to some sort of lax Australian ‘standard’?

Would you trust the brakes in your automobile if they have not been tested or even approved for use?

And you’re supposed to trust the TGA, especially now when some sort of self-testing kit is going to be available regarding the current global ‘health’ situation?

This is specially concerning given the fact that from the beginning Australia has been using a flawed or rather inaccurate test method to determine so called ‘cases’ that all governments go on about.

See the story the government would rather you forget from November 2017 by smh.com.au of the headline:

Australia's health watchdog accused of 'too close' relationship with industry

Australia's drug and medical device watchdog, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, needs a complete overhaul to distance it from the health industry and allow consumers to sue it for negligence, say academics and consumer advocates after the regulator quietly announced moves to classify all pelvic mesh devices high risk after years of controversy.

"The current regulatory framework is a complete bypass of the interests of consumers. They don't have a stake at the table," said University of Canberra academic Wendy Bonython, after the TGA said the new classification would mean "higher evidentiary requirements" before new devices are approved for use in Australia, and for existing approved devices.

Illustration above: Australian Pelvic Mesh Support Group members fought for a Senate inquiry into how pelvic mesh devices were cleared for use in Australia.

The move comes more than a decade after many pelvic mesh devices were cleared for use by the TGA with little or no independent evidence of safety and efficacy.

The announcement on the TGA's website on October 26 also follows evidence at a Senate inquiry about the devastating and permanent consequences of mesh surgery for thousands of Australian women, and a class action by women against mesh manufacturer Johnson & Johnson.

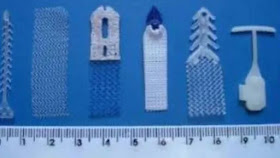

A selection of pelvic mesh devices cleared for release in Australia and overseas for use in women.Dr Bonython and University of Canberra associate professor Bruce Arnold told the Senate inquiry the TGA's "industry-funded model of regulation" raises questions about the regulator's independence in the wake of a string of device scandals, including pelvic mesh, joint prostheses, breast and contraceptive implants, cardiac stents and pacemakers.

The failures indicate "systemic weaknesses in the prevention of and response to foreseeable harms", with the "enormous" cost borne by individuals and the broader community, they said.

"Trying to run a regulator on a shoestring, particularly a medical device regulator, is a bit of a false economy because if we're not investing in the regulator, chances are we're going to be subsidising its failures through things like the National Disability Insurance Scheme or Medicare, or lack of productivity," Dr Bonython said.

"There needs to be a clear break between the regulator and the parties they're trying to regulate."

The two academics called on the Senate inquiry to investigate legislated indemnity provisions that protect the TGA from being sued for negligent performance of its regulatory functions.

"The TGA can't be sued for negligence. It doesn't matter how negligent the regulator, it can get away with it, which is problematic because it removes any incentive towards carefulness," Dr Bonython said.

There was a "lack of political will" to make hard decisions to protect consumers, she said.

"We've been writing about this since 2010. In that time we've seen a number of device scandals, inquiries, class actions, but we haven't actually seen much in the way of meaningful action on the floor of parliament. This is looking like a recurring pattern. Why are we getting so many dodgy implants?"

The medical profession's "fair degree of lobbying power" and pharmaceutical companies as "big ticket players in the economy" were issues when it came to consumer protections, she said.

In evidence to the Senate inquiry, Dr Bonython said the TGA's approval of some devices, including pelvic mesh devices, on the basis of post-market monitoring was "problematic".

"At the very least it needs to be flagged as an experimental device until such time as there is a sufficient body of evidence indicating that it's safe to use," Dr Bonython said.

Gynaecologist Professor Christopher Maher, who first raised concerns about a pelvic mesh device in a paper in 2003, told a Senate inquiry hearing that the TGA was "the first level of oversight" for new devices and drugs, but pelvic mesh devices were approved without independent evidence of safety and efficacy.

Professor Maher told the inquiry he had "sort of a frosty relationship" with the TGA after raising serious questions about pelvic mesh devices during internal reviews by the regulator over a number of years.

"With hindsight, I think, everyone in the TGA would say they wished that they didn't allow these products through when there wasn't much evidence supporting those products," Professor Maher said.

The Federal Government-funded Consumers Health Forum of Australia, representing state consumer health groups, told the Senate inquiry the approval and marketing of pelvic mesh devices for more than a decade represented a "catastrophic system-wide failure", that included the TGA and its processes.

The TGA's adverse events reporting system to detect serious drug and device problems was described by women as "something of a black hole, with lots of information going into it but nothing visible coming out", the forum said.

Forum member and Victorian Health Issues Centre chief executive Danny Vadasz said the nexus between companies, the medical profession and the TGA was "insidious and undermines the integrity of our regulatory system".

"What quality of guardianship can you expect when the poacher is paying the wages of the gamekeeper?" Mr Vadasz said.

"The government must act to give the TGA financial independence from big pharma, to raise the evidentiary bar on safety and quality and to be held accountable for its singular purpose, to protect the safety of the public.

"Until we have such legislative reform public health will remain hostage to the sales and marketing targets of medical device manufacturers."

Forum member and Western Australian Health Consumers Council executive director Pip Brennan said the "appalling outcomes some women had experienced from TGA-approved pelvic mesh implants highlights a fundamental flaw in how our regulatory system is working".

"The recent quiet announcement of the up-classification of mesh devices still does not reassure as there is no guarantee consumers will be provided with relevant consent documentation and there is still no commitment to create a register to track the devices being implanted," Ms Brennan said.

"There must be a separation between income for our regulatory body, and the approval of devices. No one has a higher stake in a medical device than the patient who is having something permanently implanted, and yet consumers are not at the decision-making table of the TGA. This needs to change."

Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt's office referred questions to the TGA, which "totally rejected" claims it had a too-close relationship with industry because of its funding model.

"Industry has no say whatsoever in how TGA spends the revenue it receives from other industry charges. This system has been in place for more than 20 years and there has been no evidence of any sort of 'regulatory capture'," a spokesperson said.

"Other medicines and device regulators internationally also are fully or significantly funded by industry fees and charges and operate in the same way. This takes the burden off the taxpayer for such time-consuming scrutiny.

"It is accepted as best regulatory practice for regulators to have a good understanding of and working relationship with the regulated entities. So, while the TGA meets frequently with industry and other stakeholders, including consumer and healthcare groups, it maintains a professional but arm's length relationship and does not include them in any final decision-making once consultations are completed."

The TGA said it accepted evidence from an expert committee in 2008 that recommended it continue to monitor meshes, but the reported rate of complications was low. By 2013 an internal TGA report acknowledged its adverse event reporting system only received 10-20 per cent of all adverse events because it relied on manufacturers to report complications.

The TGA has not prosecuted one mesh manufacturer for failing to report complications, despite it being a criminal offence carrying a jail term and substantial fine.

In 2014 the regulator cancelled the first of more than 40 pelvic mesh devices and increased monitoring and reporting requirements for remaining devices.

In its statement the TGA said "it must be emphasised that the TGA does not regulate clinical practice and decisions by doctors to use these devices".

No comments:

Post a Comment